Knee Injuries

Knee injuries are painful and inconvenient. It is important to quickly identify what your injury is and what your treatment options may be. Below you will find symptoms, treatment options, and other information about various knee injuries. Please contact us to request an orthopaedic evaluation.

Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL) Injuries

One of the most common knee injuries is an anterior cruciate ligament sprain or tear.

Athletes who participate in high demand sports like soccer, football, and basketball are more likely to injure their anterior cruciate ligaments.

If you have injured your anterior cruciate ligament, you may require surgery to regain full function of your knee. This will depend on several factors, such as the severity of your injury and your activity level.

Anatomy

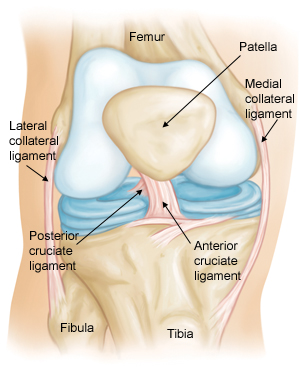

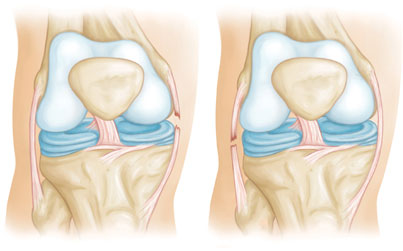

Three bones meet to form your knee joint: your thighbone (femur), shinbone (tibia), and kneecap (patella). Your kneecap sits in front of the joint to provide some protection.

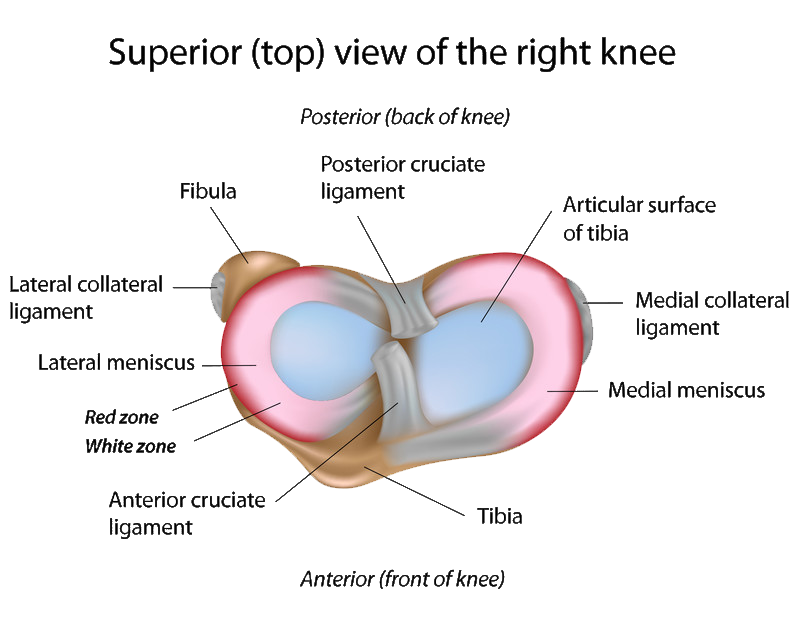

Bones are connected to other bones by ligaments. There are four primary ligaments in your knee. They act like strong ropes to hold the bones together and keep your knee stable.

Collateral Ligaments

These are found on the sides of your knee. The medial collateral ligament is on the inside and the lateral collateral ligament is on the outside. They control the sideways motion of your knee and brace it against unusual movement.

Cruciate Ligaments

These are found inside your knee joint. They cross each other to form an “X” with the anterior cruciate ligament in front and the posterior cruciate ligament in back. The cruciate ligaments control the back and forth motion of your knee.

The anterior cruciate ligament runs diagonally in the middle of the knee. It prevents the tibia from sliding out in front of the femur, as well as provides rotational stability to the knee.

Description

About half of all injuries to the anterior cruciate ligament occur along with damage to other structures in the knee, such as articular cartilage, meniscus, or other ligaments.

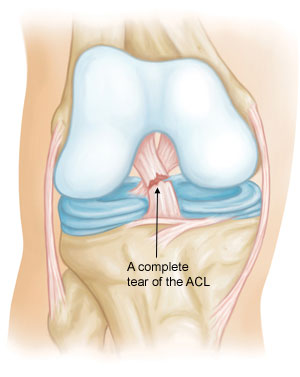

Injured ligaments are considered “sprains” and are graded on a severity scale.

Grade 1 Sprains. The ligament is mildly damaged in a Grade 1 Sprain. It has been slightly stretched, but is still able to help keep the knee joint stable.

Grade 2 Sprains. A Grade 2 Sprain stretches the ligament to the point where it becomes loose. This is often referred to as a partial tear of the ligament.

Grade 3 Sprains. This type of sprain is most commonly referred to as a complete tear of the ligament. The ligament has been split into two pieces, and the knee joint is unstable.

Partial tears of the anterior cruciate ligament are rare; most ACL injuries are complete or near complete tears.

Cause

The anterior cruciate ligament can be injured in several ways:

- Changing direction rapidly

- Stopping suddenly

- Slowing down while running

- Landing from a jump incorrectly

- Direct contact or collision, such as a football tackle

Several studies have shown that female athletes have a higher incidence of ACL injury than male athletes in certain sports. It has been proposed that this is due to differences in physical conditioning, muscular strength, and neuromuscular control. Other suggested causes include differences in pelvis and lower extremity (leg) alignment, increased looseness in ligaments, and the effects of estrogen on ligament properties.

Symptoms

When you injure your anterior cruciate ligament, you might hear a “popping” noise and you may feel your knee give out from under you. Other typical symptoms include:

- Pain with swelling. Within 24 hours, your knee will swell. If ignored, the swelling and pain may resolve on its own. However, if you attempt to return to sports, your knee will probably be unstable and you risk causing further damage to the cushioning cartilage (meniscus) of your knee.

- Loss of full range of motion

- Tenderness along the joint line

- Discomfort while walking

Doctor Examination

During your first visit, your doctor will talk to you about your symptoms and medical history.

During the physical examination, your doctor will check all the structures of your injured knee, and compare them to your non-injured knee. Most ligament injuries can be diagnosed with a thorough physical examination of the knee.

Imaging Tests

Other tests which may help your doctor confirm your diagnosis include:

X-rays. Although they will not show any injury to your anterior cruciate ligament, x-rays can show whether the injury is associated with a broken bone.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan. This study creates better images of soft tissues like the anterior cruciate ligament. However, an MRI is usually not required to make the diagnosis of a torn ACL.

Treatment

Treatment for an ACL tear will vary depending upon the patient’s individual needs. For example, the young athlete involved in agility sports will most likely require surgery to safely return to sports. The less active, usually older, individual may be able to return to a quieter lifestyle without surgery.

Surgical Options

Rebuilding the ligament. Most ACL tears cannot be sutured (stitched) back together. To surgically repair the ACL and restore knee stability, the ligament must be reconstructed. Your doctor will replace your torn ligament with a tissue graft. This graft acts as a scaffolding for a new ligament to grow on.

Grafts can be obtained from several sources. Often they are taken from the patellar tendon, which runs between the kneecap and the shinbone. Hamstring tendons at the back of the thigh are a common source of grafts. Sometimes a quadriceps tendon, which runs from the kneecap into the thigh, is used. Finally, cadaver graft (allograft) can be used.

There are advantages and disadvantages to all graft sources. You should discuss graft choices with your own orthopaedic surgeon to help determine which is best for you.

Because the regrowth takes time, it may be six months or more before an athlete can return to sports after surgery.

Procedure. Surgery to rebuild an anterior cruciate ligament is done with an arthroscope using small incisions. Arthroscopic surgery is less invasive. The benefits of less invasive techniques include less pain from surgery, less time spent in the hospital, and quicker recovery times.

Unless ACL reconstruction is treatment for a combined ligament injury, it is usually not done right away. This delay gives the inflammation a chance to resolve, and allows a return of motion before surgery. Performing an ACL reconstruction too early greatly increases the risk of arthrofibrosis, or scar forming in the joint, which would risk a loss of knee motion.

Rehabilitation

Whether your treatment involves surgery or not, rehabilitation plays a vital role in getting you back to your daily activities. A physical therapy program will help you regain knee strength and motion.

If you have surgery, physical therapy first focuses on returning motion to the joint and surrounding muscles. This is followed by a strengthening program designed to protect the new ligament. This strengthening gradually increases the stress across the ligament. The final phase of rehabilitation is aimed at a functional return tailored for the athlete’s sport.

Non-Surgical Options

A torn ACL will not heal without surgery. But nonsurgical treatment may be effective for patients who are elderly or have a very low activity level. If the overall stability of the knee is intact, your doctor may recommend simple, nonsurgical options.

Bracing. Your doctor may recommend a brace to protect your knee from instability. To further protect your knee, you may be given crutches to keep you from putting weight on your leg.

Physical therapy. As the swelling goes down, a careful rehabilitation program is started. Specific exercises will restore function to your knee and strengthen the leg muscles that support it.

Collateral Ligament Injuries

The knee is the largest joint in your body and one of the most complex. It is also vital to movement.

Your knee ligaments connect your thighbone to your lower leg bones. Knee ligament sprains or tears are a common sports injury.

Athletes who participate in direct contact sports like football or soccer are more likely to injure their collateral ligaments.

Anatomy

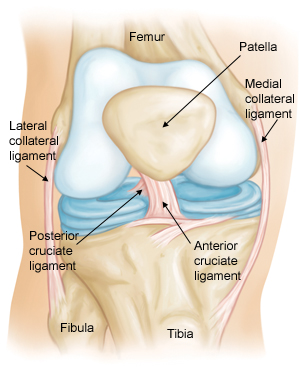

Three bones meet to form your knee joint: your thighbone (femur), shinbone (tibia), and kneecap (patella). Your kneecap sits in front of the joint to provide some protection.

Bones are connected to other bones by ligaments. There are four primary ligaments in your knee. They act like strong ropes to hold the bones together and keep your knee stable.

Cruciate Ligaments

These are found inside your knee joint. They cross each other to form an “X” with the anterior cruciate ligament in front and the posterior cruciate ligament in back. The cruciate ligaments control the back and forth motion of your knee.

Collateral Ligaments

These are found on the sides of your knee. The medial or “inside” collateral ligament (MCL) connects the femur to the tibia. The lateral or “outside” collateral ligament (LCL) connects the femur to the smaller bone in the lower leg (fibula). The collateral ligaments control the sideways motion of your knee and brace it against unusual movement.

Description

Because the knee joint relies just on these ligaments and surrounding muscles for stability, it is easily injured. Any direct contact to the knee or hard muscle contraction — such as changing direction rapidly while running — can injure a knee ligament.

Injured ligaments are considered “sprains” and are graded on a severity scale.

Grade 1 Sprains. The ligament is mildly damaged in a Grade 1 Sprain. It has been slightly stretched, but is still able to help keep the knee joint stable.

Grade 2 Sprains. A Grade 2 Sprain stretches the ligament to the point where it becomes loose. This is often referred to as a partial tear of the ligament.

Grade 3 Sprains. This type of sprain is most commonly referred to as a complete tear of the ligament. The ligament has been split into two pieces, and the knee joint is unstable.

The MCL is injured more often than the LCL. Due to the more complex anatomy of the outside of the knee, if you injure your LCL, you usually injure other structures in the joint, as well.

Cause

Injuries to the collateral ligaments are usually caused by a force that pushes the knee sideways. These are often contact injuries, but not always.

Medial collateral ligament tears often occur as a result of a direct blow to the outside of the knee. This pushes the knee inwards (toward the other knee).

Blows to the inside of the knee that push the knee outwards may injure the lateral collateral ligament.

Doctor Examination

During your first visit, your doctor will talk to you about your symptoms and medical history.

During the physical examination, your doctor will check all the structures of your injured knee, and compare them to your non-injured knee. Most ligament injuries can be diagnosed with a thorough physical examination of the knee.

Imaging Tests

Other tests which may help your doctor confirm your diagnosis include:

X-rays. Although they will not show any injury to your collateral ligaments, x-rays can show whether the injury is associated with a broken bone.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan. This study creates better images of soft tissues like the collateral ligaments.

Symptoms

- Pain at the sides of your knee. If there is an MCL injury, the pain is on the inside of the knee; an LCL injury may cause pain on the outside of the knee.

- Swelling over the site of the injury.

- Instability — the feeling that your knee is giving way.

Surgical Options

Injuries to the MCL rarely require surgery. If you have injured just your LCL, treatment is similar to an MCL sprain. But if your LCL injury involves other structures in your knee, your treatment will address those, as well.

Non-Surgical Options

Ice. Icing your injury is important in the healing process. The proper way to ice an injury is to use crushed ice directly to the injured area for 15 to 20 minutes at a time, with at least 1 hour between icing sessions. Chemical cold products (“blue” ice) should not be placed directly on the skin and are not as effective.

Bracing. Your knee must be protected from the same sideways force that caused the injury. You may need to change your daily activities to avoid risky movements. Your doctor may recommend a brace to protect the injured ligament from stress. To further protect your knee, you may be given crutches to keep you from putting weight on your leg.

Physical therapy. Your doctor may suggest strengthening exercises. Specific exercises will restore function to your knee and strengthen the leg muscles that support it.

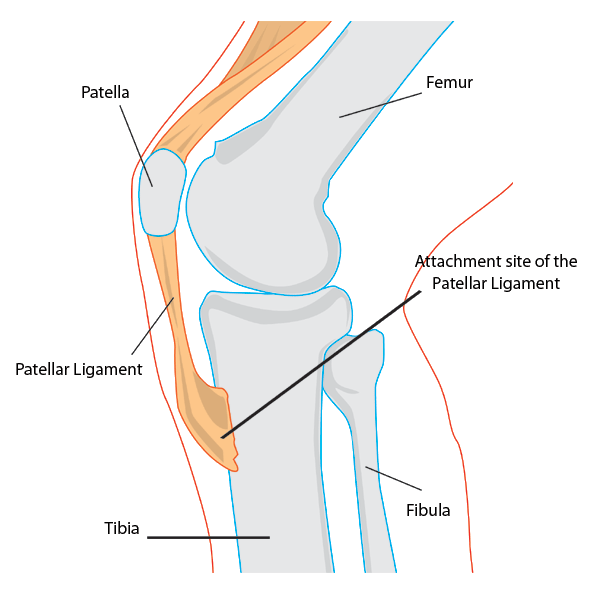

Adolescent Knee Pain (Osgood-Schlatter disease)

Osgood-Schlatter disease is a common cause of knee pain in growing adolescents. This disease causes inflammation of the area where the tendon from the kneecap (patellar tendon) attaches to the shinbone (tibia), just below the patient’s knee. Commonly seen in those who participate heavily in sports activities, it can also occur in less active adolescents. Teenagers are going through rapid periods of growth and the structure of bones, tendons and muscles changes rapidly, it’s during this period that injury is more likely, especially when exercise is putting additional tension on the knee.

Child and adolescent bones contain a unique area known as the growth plate, which consists of cartilage and is situated at the ends of the bones. By adulthood, the plate has hardened to become a solid bone. Growth plate fractures are handled differently than other fractures.

Tendons (the strong tissue that connects muscles to the bones) generally attach to growth plates, and a hard bump called the tibial tubercle covers the growth plate at the end of the tibia. The quadriceps, the muscles in front of the thigh, attach themselves to the tibial tubercle. Because children are active the quadriceps cause tension on the patellar tendon, which in turn pulls on the tibial tubercle. This repeated action can lead to inflammation of the growth plate and the bump of the tibial tubercle becoming more pronounced.

Symptoms

If the adolescent is experiencing pain when playing sports or during every day activities, they may be experiencing Osgood-Schlatter Disease. This could be evident in one or both knees. Other signs may include:

- Knee pain and tenderness

- Swelling

- The feeling of tight muscles in the front or back of the thigh

Surgical Options

Some adults have residual Osgood-Schlatter Disease which can cause painful ossicles (small fragments of bone) that can be pinched by the patellar tendon against the front of the knee, causing painful inflammation. If this is the case, surgery may be necessary. Contact Dr. Sima if you or your child is experiencing symptoms of Osgood-Schlatter Disease to discuss your surgery options.

Non-Surgical Options

It’s reassuring to know that in most cases of Osgood-Schlatter disease, non-surgical treatment such as medication, stretching, and conditioning exercises may relieve symptoms and allow normal activities to resume-though the tibial tubercle will remain pronounced.

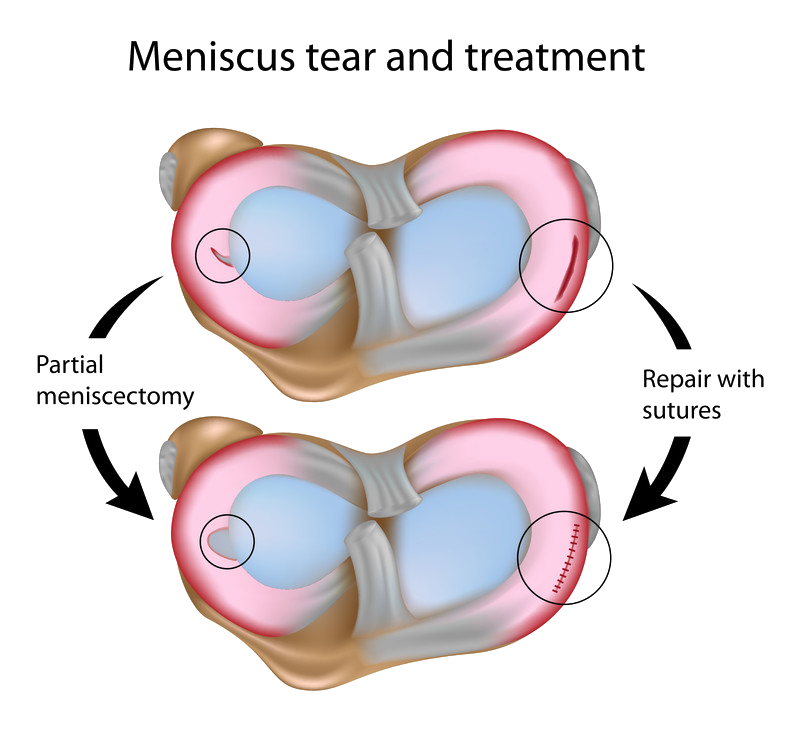

Torn Meniscus

The meniscus can be injured by trauma or through a degenerative process. Sports injuries account for most trauma-induced meniscal tears, usually from a bend-and-twist motion. Other injuries may be due to wear-and-tear of more brittle cartilage, a byproduct of the aging process. Often meniscal tears occur at the same time other components of the knee are injured. A common injury among athletes involves simultaneously the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL), the medial collateral ligament (MCL), and the meniscus.

In part due to the “C” shape of the meniscus, tears occur in a number of different locations. Flap, transverse, torn horn, and bucket handle rank among the most common tears.

Symptoms

There may have been a popping sound when the injury occurred. After that, pain and swelling or tenderness usually sets in. Other symptoms include an inability to move the knee normally or to walk without pain. For some, an injured knee may occasionally lock at a 45° angle temporarily.

Surgical Options

The inner 2/3 of the meniscus has low blood supply, and without the nutrients provided by blood, these tears cannot heal. Tears of this type usually occur in the worn out cartilage, which is thinner and weaker. Because the pieces cannot reattach back together, tears in this region will need surgical intervention.

Surgery for meniscus tears involves trimming away the damaged meniscus or repairing the tear through stitching. It is performed through arthroscopic surgery.

Knee arthroscopy is one of the most commonly performed surgical procedures. In it, a miniature camera is inserted through a small incision in the knee. This provides a clear view of the inside of the knee. The orthopaedic surgeon inserts miniature surgical instruments through other incision points to trim or repair the tear.

Non-Surgical Options

Your orthopaedic surgeon will do a complete physical examination and order diagnostic tests such as X-rays and MRI to determine the size of your tear, it’s location, and the type of tear. If the tear is in the outside 1/3 of the meniscus, which is rich in blood supply, the good news is the tear can often be repaired without surgery.

Kneecap Fracture

One of the most common knee injuries is fracture of the patella (kneecap). Impact to the front of the knee is the most common cause, such as falling or being hit by a strong object. The patella acts as shield to the knee joint and due to its position, can be injured relativley easily.

Types of Patella Fractures

Stable fracture – where the patella has not moved out of alignment. The bone ends are still lined up correctly (non-displaced). In this case, the bones will generally stay in place on their own during healing.

Displaced fracture – where the bone has become misaligned. This type of fracture often requires surgery to put the pieces back together.

Comminuted fracture – in this case, the bone has shattered into several pieces (usually 3 or more)

Open fracture – the most serious fracture, this occurs when the skin has been broken and the bone is exposed. Along with bone damage, ligaments, muscles, and tendons often suffer damage, meaning that there is a high risk of complications and longer healing time.

Symptoms

If a patient experiences these symptoms following severe impact to the knee bone, it may indicate a fracture has taken place

- Swollen and bruised knee cap region.

- Pain when moving the knee (in different directions)

- Difficulty extending or raising the leg in a straight position

- Appearance of deformity in the knee cap region (this is due to misaligned fragments)

- Tenderness and pain when touching the kneecap region

Surgical Options

Surgery is generally needed to replace unstable, displaced, and open fractures, or injuries where tendons and ligaments have also been damaged. Dr. Sima and his team are experts in treating these conditions and will explain the best options.

Open Reduction Internal Fixation Surgery

The purpose of Open Reduction Internal Fixation Surgery is to put the pieces of broken bones back together.First, the surgeon will makes an incision over the kneecap to determine how well the broken pieces can be put back together. Unfortunately in some cases, repair is impossible and the surgeon will remove them. In instances where the repair is possible, the pieces of patella are put back together and in place using metal screws and/or wires. These stainless steel components can stay in the body permanently and hold the bones in the correct position while they heal.

Recovery time varies dramatically for each patient, depending on the extent of damage and intervention required but the outcome is usually very favorable.

Non-Surgical Options

In the case of a stable fracture, the leg may be put in a brace, splint, or cast to prevent it from moving during the healing process. NSAID pain medication is often prescribed and with good care the fracture should take 6 – 8 weeks to heal.

Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome (Runner’s Knee)

Patellofemoral pain syndrome, also known as “runner’s knee,” is the most common of all running injuries.

Pain and stiffness are common and may cause disruption to everyday activities. Athletes (especially women) are most at risk of developing this condition, as vigorous exercise can cause strain. Misalignment of the kneecap is also a contributing factor.

Symptoms

The patient may experience dull, aching pain around the front of the kneecap (the patella) where it connects to the lower end of the thighbone (the femur). The pain may worsen when going up or down stairs, squatting, or kneeling.

Surgical Options

Arthroscopy, which involves the use of a small, pencil-sized camera, can be used to remove small fragments of kneecap cartilage. Realigning the kneecap is also an alternative, and this is done by opening the knee and reducing the abnormal pressures on the cartilage.

Non-Surgical Options

Treatment of patellofemoral pain depends on the underlying cause. The most important way to improve the condition is rest and rehabilitation. In some cases, surgery can correct the underlying condition and improve support to the knee. There are new, emerging surgery alternatives for many serious knee conditions. Dr. Sima will evaluate each patient’s unique condition to determine if one of these may be an option. At-home care involves rest, ice, compression, and elevation.

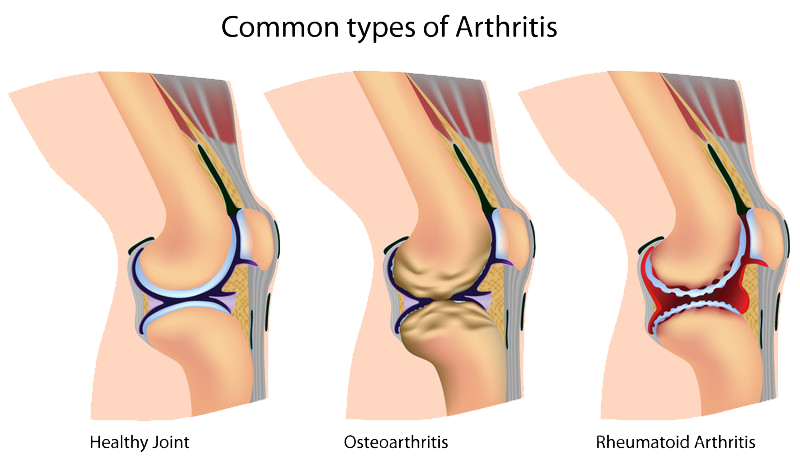

Arthritis of the Knee

Arthritis is a chronic degenerative condition, meaning that the over time, functionality of the joint will deteriorate and surgery will eventually be required. Arthritis can cause severe knee pain and have a major impact on day-to-day living. If there is difficulty bending the knee and swelling, arthritis may be the culprit.

Common types of arthritis include:

Rheumatoid Arthritis

Rheumatoid arthritis is an autoimmune disease, causing thickness to the tissue around the joint and subsequent inflammation. This chronic inflammation can often lead to loss of cartilage or severe damage. Rheumatoid arthritis accounts for around 15% of all arthritis cases.

Post-Traumatic Arthritis

Damage caused by a serious knee injuries such as bone fractures or ligament tears can lead to arthritis.

The most common type of arthritis, osteoarthritis is caused by progressive wearing of the cartilage in the knee joint. It is more frequently diagnosed in those over 50 because of long term wear and use of the joint. Osteoarthritis of the knee is a painful condition that can limit motion, cause swelling, deformity, stiffness, and weakness on a constant basis. Patellofemoral Arthritis is a unique form of osteoarthritis affecting the kneecap. Patellofemoral arthritis occurs when the articular cartilage starts to wear away and becomes inflamed. The cartilage eventually becomes frayed, and in time the bone underneath may become exposed. Movement can be very painful because of the rough surface. Cartilage deterioration may be caused by fracture to the kneecap, or dysplasia when the patella isn’t settled correctly in place. The increased stress on the cartilage causes it to wear down.

Causes of Arthritis

- Age – wear and tear over the years

- Family history – genetic predisposition to arthritis

- Weight – excess weight can cause extra strain and pressure on joints

- Previous injuries and illness – can cause deterioration of cartilage leading to arthritis

Symptoms

If you are experiencing the following, arthritis may be the cause:

- Pain during activity that eases slightly when resting

- Swelling in the knee area

- Feeling of burning or heat in the knee joint

- Stiffness in the knee, which may be worse in the morning or after inactivity

Surgical Options

Osteoarthritis is a chronic disease. Unfortunately, no cure has yet been found, though there are many treatments- including surgery– that can help manage the symptoms.

Because there is no cure, alternative treatments can only help manage the pain and other symptoms.

Joint surgery aims to replace or repair severely damaged joints. This may be achieved through:

Arthroscopy

Arthroscopy involves a surgeon making a small incision in your knee to clean and remove loose pieces of cartilage. Results can be unpredictable and this procedure isn’t often recommended.

Partial (Unicompartmental) Knee Replacement

This is where only the worn out/damaged part of the knee is removed and replaced, usually the femoral-tibial joint or the patella/femur joint. partial knee replacement surgery is less invasive and has a faster recovery time than full knee replacement.

Total Knee Replacement Surgery

Total knee replacement (TKR) is considered when other options have failed, or are not considered suitable. This surgery is considered the most successful of all surgical procedures. The results are generally outstanding, with 90 – 95% pain reduction and extremely low complication rate of only 1-2%. The synthetic joint has a lifespan of over 20 years.

Osteotomy

Osteotomy is performed rarely these days, and generally in younger patients with misalignment of the knee. In this procedure, the bone is cut and reoriented to realign the knee.

A consultation with our orthopaedic specialist will help determine your suitability for surgery.

Non-Surgical Options

There are many surgery alternatives emerging for a variety of knee injuries. While a consultation is the best way to get the full picture of all available treatment options, autologous platelet rich plasma is one option worth discussing with Dr. Sima. Check out an informative video of this therapy here!

As with other arthritic conditions, initial treatment of arthritis of the knee is nonsurgical. Your doctor may recommend a range of treatment options, including:

- Physical activity

- Stretching & strengthening exercises

- Weight management

- Anti-inflammatory and pain relief medication such as NSAIDS, cortisteroids, or hyaluronic acid

- Physical and occupational therapy

- Equipment such as braces, splints, or orthotics.

Osteochondral Defects of the Knee

A chondral defect occurs when there is damage to the articular cartilage in the knee (this is the cartilage that lines the end of the bones). An osteochondral defect is damage that involves both the cartilage and a piece of underlying bone.

Causes of Osteochondral Defects

- acute traumatic injury to the knee

- underlying disorder of the bone.

This is distinctly different than arthritis and should be thought of differently, as the treatments are significantly different. Unfortunately, an isolated cartilage defect, without any underlying bone attached to the fragment, is generally not repairable. The cartilage is often not viable when it is separated from the bone and therefore must be removed, which can be done with an arthroscopic procedure. However, the now-exposed bone should be treated, if possible, to attempt to stimulate growth of new cartilage. Some healthy flaps of cartilage can be repaired by special techniques. This would need to be discussed in detail with your surgeon.

One technique for treating isolated cartilage defects is called a “microfracture.” This technique is suitable for younger to middle age patients with very focal areas of cartilage loss (typically less than 2 square centimeters) and where the remaining cartilage is healthy. During a microfracture (which is typically done arthroscopically), tiny holes are made in the bone to create tunnels to the underlying bone marrow and natural stem cells. Through these channels, the stem cells flow into this area of bone and coat the area where the cartilage is lost. Over time these cells can develop into a new form of cartilage. This process is delicate and requires optimum conditions to be routinely successful. Therefore, certain protocols will need to be followed after surgery to protect this area as well as contour the newly forming cartilage.

Another technique, typically reserved for larger areas of loss and some forms of osteochondral defects, is to perform a transplant procedure. Several types of transplants can be performed, including taking small plugs of bone and cartilage from other locations in the knee and filling this defect. Often what is required is the use of a fresh donor graft of bone and cartilage that is specifically matched to the size and dimensions of the defect. This can often take months until a suitable donor is available.

An osteochondral defect that is in the early stages may be suitable for a repair technique to keep the native bone and cartilage. This would be the optimal scenario. This requires a detailed evaluation to be performed to assess the integrity of the remaining cartilage, the underlying bone, and to look for evidence of healing capacity.

Numerous factors are considered when evaluating these disorders. A comprehensive physical exam is required, as are specialized X-rays and an MRI. Occasionally, a specialized test called a bone scan will be utilized to identify if the underlying bone is healthy and prepared for certain techniques.

Surgical Options

Treatment depends upon the size of the defect and the condition of the overlying cartilage. If the defects are small, surgical treatment involves drilling in the lesion and filling it with special “cement” designed for bones. The bone defect can therefore be treated without causing damage to the cartilage. If the cartilage is already damaged, microdrilling or micropicking of the surface of the bone is preferable and stimulates the formation of fibrocartilage, which will replace the original cartilage that has been lost.

Larger lesions require a different method to replace the damaged cartilage. Osteochondral autologous transfer (OATS) is a procedure where a graft of bone and cartilage is taken from the knee and implanted into the site of the defect.

Non Surgical Options

Osteochondral defects are not typically repairable, and surgery is normally recommended.

My knee was bent and I could not straighten it because of a sports injury. But then, you operated on me and when I awoke, all the pain was gone. After a brief recovery, I could, once more walk and run as I did before my injury. I have a tiny scar on my knee. Your skilled hands performed what amounts to a miracle in my life and I have been grateful to you every day since that time.

-Marcia Triggs